Always Courageous Collection

The U.S. Navy in the times of the world wars: sailors, navy uniforms, awards, and main batteries.

The overall collection was comprised of four sub-collections. Each sub-collection granted a unique reward. There was a separate reward for obtaining all 16 items. Items may be bought for 4 duplicates.

Contents

Collections

"Always Courageous" Collection - Naval Commanders

George Dewey (1837–1917) was an admiral of the U.S. Navy (1903). During his time at the naval academy, he earned a reputation for being somewhat of a scrapper. However, during the Civil War (1861–1865), he proved himself to be a courageous combat officer whose ships frequently found themselves in the heat of battle. The three decades that followed the war were occupied by routine service, then the war that made the future admiral go down in American history began.

At the end of 1897, when the conflict between Spain and the United States was about to turn into direct confrontation, Commodore Dewey was assigned to the Asiatic Squadron. The Commodore hoisted his pennant over USS Olympia, a brand-new protected cruiser. With his usual energy, Dewey spent several months preparing his ships and their crews for combat. On May 1, 1898, the squadron, led by USS Olympia, entered Manila Bay, silenced the shore batteries and, within a period of just several hours, turned the entire Spanish Pacific fleet into burning wreckage—demonstrating the power of modern quick-firing artillery. Without losing a single man, and in just one battle, Dewey ensured victory in the whole theater of operations and became a national hero. The special rank of Admiral of the Navy—the highest rank in the history of the United States—was established just for him in 1903.

William Sims (1858–1936) was an admiral of the U.S. Navy (1918), and one of the main reformers of the American fleet. In the first decades of the 20th century, he made the U.S. Navy one of the strongest fleets in the world. He was the U.S. Navy’s Inspector of Naval Gunnery, committed to improving the designs of American battleships and reforming their gunnery, based on the recent advances in European naval engineering. Later on, he commanded a destroyer flotilla and the most modern battleship of the time—Nevada.

When the United States joined World War I in 1917, he took command of the entire U.S. naval force in Europe. He established fruitful cooperation with the British Command, and it was thanks to this that American ships actively took part in joint naval operations, contributing a great deal to their common victory. After the war, he became president of the "brain" of the fleet—the Naval War College—where he introduced wargames into the system of preparing flag officers. This allowed the future naval commanders of World War II to practice and hone their skills.

Willis Lee (1888–1945) was a vice admiral of the U.S. Navy (1944). It’s quite possible that at that time there had been no other officers in the history of the United States Navy who could claim to be a true marksman with a pistol, rifle, and 16-inch guns. After joining the service, he spent 25 years defending the honor of the United States Navy in various shooting competitions. During the 1920 Summer Olympics, Lee earned five gold medals. He managed to combine that path with his service on various ships and in military industry enterprises. When he reached the senior ranks, he was asked to join the Department of the Navy, where he oversaw everything related to fleet training.

In the first months following the United States' entry into World War II, Lee was an assistant chief of staff to the commander in chief of the US Navy, before being sent to the Pacific to command a battleship division. In November of 1942, when the Guadalcanal campaign was on the line, it was Willis Lee who tipped the balance in favor of the Americans by destroying Japanese battleship Kirishima. He relied heavily on radar to achieve this. At the same time, the admiral’s flagship—USS Washington—managed to evade detection by the enemy. In the two and a half years that followed, the battleships under Lee’s command continued to rain fire down upon enemy positions. However, the admiral didn’t live to see the surrender of Japan, as he died of a heart attack several days prior to it.

Thomas Kinkaid (1888–1972) was an admiral of the United States Navy (1945), and the son of a naval officer. During the early stages of his career, he discovered his interest in gunnery. This was supported by his father’s colleague, William Sims, a future admiral himself. Kinkaid soon became an acknowledged expert in naval gunnery and fire control. He worked in industrial enterprises where various armament types were produced, and alongside this, he worked in the corresponding divisions of the Navy Department. Among the ships on which he honed his skills were cruiser Indianapolis, and battleships Arizona and Colorado.

During the early stages of the war against Japan, Kinkaid took part in almost all key battles in the Pacific Ocean. It took him a year to advance from cruiser squadron commander to commander of a powerful task force that included ships of all major types. Coral Sea, Midway, Eastern Solomons, Santa Cruz Islands—in these fierce battles, new tactics with carrier aviation playing a key role were being forged. At the end of 1943, Kinkaid took lead of the renowned Seventh Fleet. In this role, having become a master of complex tactical operations, he traversed from New Guinea to the Philippines, partaking in an endless number of battles.

Reward

Completing this sub-collection provides the following rewards:

| Icon | Name |

|---|---|

|

Stars'n'Stripes |

World War Service Medals

"Always Courageous" Collection - World War Service Medals

The winning powers designed their medals for World War I participants according to common criteria—they all had a winged figure of Victoria, the goddess of victory, on the obverse side, and the same ribbon. In the U.S.A. this medal was established through orders issued by branches of the Armed Forces. The Navy issued it in June 1919. The Victory Medal was awarded to military personnel for service between April 6, 1917, and November 11, 1918—the day on which the U.S. Congress declared war on Germany, and the day on which the Armistice of Compiègne between Germany and the Allies was signed accordingly.

Both the U.S. Army and Navy established a large number of distinction marks for the World War I Victory Medal in the form of metallic clasps.

For all personnel who fought in the war, the Navy instituted 19 clasps that specified their ship type, duty, or place where they served. The list of ships whose crews had the right to wear one of the clasps on their medals included 1,388 pennants. Thus, the "GRAND FLEET" inscription meant that its owner had served from December 9, 1917, through November 11, 1918, on one of the U.S. dreadnoughts that formed part of the British Grand Fleet in the Northern Sea. Ownership of a clasp like this would be demonstrated by a small bronze star worn on the medal's ribbon bar.

A special type of individual award in the Navy was the official citation for exemplary service from the naval minister. It was issued to those whose distinction during World War I didn't meet the requirements for one of the highest awards—the Medal of Honor, the Navy Distinguished Service Medal, or the Navy Cross. The person mentioned in a citation like this had the right to wear a silver star on the Victory Medal's ribbon. It was located above the clasp on the ribbon, and before other stars on the ribbon bar.

The Victory Medal was the most widespread American award until the beginning of World War II. In the U.S. Navy alone, about half a million servicemen received it.

The medal was established by a presidential executive order on November 6, 1942. It was awarded to any member of the United States Armed Forces who had served in the Asiatic-Pacific Theater between December 7, 1941 and March 2, 1946. The boundaries of the Asiatic-Pacific Theater in the north and south met the North and South Pole, in the east it went through the Pacific Ocean not reaching 320 kilometers to the American continent, and in the west its border went along the 60th meridian east longitude, slightly departing from it only along the eastern boundary of Iran. At first, the medal existed only as a service ribbon. A full medal was authorized in 1947. The first person to receive it was Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in the Southwest Pacific Area.

In the ribbon, the combination of the main yellow (gold) color with the red, white and blue stripes in the center match the colors of the service ribbon of the American Defense Service Medal, symbolizing continuity in that respect with the entry of the U.S. into World War II. The red and white stripes on the sides symbolize the colors of the enemy flag—Japan. For servicemen who took part in military operations, there were special star-shaped decorations for service in campaigns—the main operations of World War II. Starting with Pearl Harbor, there were 43 officially recognized U.S. Navy campaigns of 1941–1945 in the Pacific Theater of Operations. Each of them was denoted by a bronze star attached to the service ribbon and ribbon bar. When the number of such stars reached five, they were replaced by a silver star.

Navy servicemen who took part in combat as part of the U.S. Marine Corps and its fleet units had the right to a wear a special decoration. During World War II, it was mainly the personnel of Naval Construction Battalions that supported landing operations in the Pacific. The decoration was a miniature emblem of the U.S. Marine Corps that was attached to the center of the ribbon and the ribbon bar. The stars for campaigns were usually placed at the sides.

The medal was established by a presidential executive order on June 28, 1941. It was awarded to service members who had served on active duty between September 8, 1939, and December 7, 1941, inclusive—from the day when Franklin D. Roosevelt had declared a limited national emergency due to the outbreak of war in Europe, until the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor that incited the United States to enter World War II.

The main yellow (gold) color of the ribbon bar symbolized a golden opportunity for the U.S. youth to serve their country's flag, which was represented by the combination of red, white, and blue lines on both sides. The American Defense Service Medal could be worn with a range of distinctive insignias, and some of them were intended only for sailors.

Personnel of the United States Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard had the right to wear a bronze clasp with "FLEET" inscribed on the medal's ribbon for service on the high seas while regularly attached to any ships and vessels of the Atlantic, Pacific, or Asiatic Fleets, as well as those of the Naval Transport Service and ships operating directly under the Chief of Naval Operations.

The "A" Device was the letter "A" without serifs that could be attached to the ribbon of the American Defense Service Medal. It was awarded to any members of the United States Navy, Marine Corps, or Coast Guard who served during actual or potential belligerent contact with the Axis Powers in the Atlantic Ocean between June 22 and December 7, 1941. The first date corresponded to the day on which U.S. marines were sent to occupy neutral Iceland. It was essentially an award for participants of the "undeclared war" that the U.S. Navy fought against the Kriegsmarine in order to help Great Britain at the beginning of the Battle of the Atlantic.

The medal was established by a presidential executive order on November 6, 1942. It was awarded to all military service members who had performed military duty between December 7, 1942, through March 2, 1946, in the European theater of World War II. Geographically, its boundaries were defined to include both North Africa and the Middle East. Initially, the award was worn only as a ribbon—the medal itself was designed only in 1946. The first recipient of the medal was Army General Dwight Eisenhower on July 24, 1947, in recognition of his service as Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force in Europe during World War II.

The color combination on the medal's ribbon, approved by the U.S. Department of Defense, had a thorough explanation. The brown color represented the sands of Africa and green represented the European fields. The red, white, and blue stripes at the center were taken from the American Defense Service Medal ribbon and referred to the continuation of American defense after the U.S. entered World War II. The green-white-red and black-and-white stripes represented the enemy—Italy and Germany.

Personnel who had served on the front line were awarded special distinction insignia—stars—for the main U.S. campaigns in which they took part during World War II. The U.S. Navy carried out nine campaigns in the European theater of war. They were mostly large landing operations in the Mediterranean, Allied landings in Normandy, and the defense of naval communication routes. Each of them was denoted by a bronze star attached to the service ribbon and ribbon bar. When the number of such stars reached five, they were replaced by a silver star.

Reward

Completing this sub-collection provides the following rewards:

| Icon | Name |

|---|---|

|

Wings |

Main Battery of Battleships

"Always Courageous" Collection - Main Battery of Battleships

South Carolina and Michigan, the first American dreadnoughts, each carried a main battery of eight 305 mm/45 caliber Mark 5 guns in four Mark 7 twin-gun turrets. The Americans were the first in the world to adopt a superfiring gun arrangement, enabling their dreadnoughts to deliver a sideways salvo similar to that of the famous British "pioneering ship" that carried two guns more. However, just like the English Dreadnought was equipped with guns and mounts from the preceding Lord Nelson-class pre-dreadnought battleships, the first American battleships also carried guns and turrets that already had a record of service on the Connecticut- and Mississippi-class pre-dreadnought battleships. Later, that same artillery, virtually unchanged, appeared on the succeeding two pairs of dreadnought battleships of the United States Navy, belonging to the Delaware and Florida classes. At an elevation of 15 degrees, the Mark 5 guns could fire a 394 kg shell approximately 18,300 m, with 100 rounds available for each gun. By all these measures, South Carolina's main battery guns outmatched Dreadnought's 305 mm guns. But alas, although the U.S.A. commenced development of a battleship carrying main guns of the same caliber as early as 1902—earlier than Great Britain—by the time the first American dreadnought-type warship was completed in 1910, the Royal Navy already had as many as five dreadnoughts and three battlecruisers in service.

Entering service in 1916, Pennsylvania and Arizona were the first U.S. super-dreadnoughts to have their entire main batteries placed in triple turrets. Prior to them, battleships New York and Texas carried their main batteries in five twin turrets, with Nevada and Oklahoma both having pairs of twin raised and triple end turrets. All these ships were equipped with 356 mm/45 Mark 1 guns, the first artillery assets with such a caliber in the U.S. Navy. Pennsylvania-class battleships disposed of twelve such guns placed in four turrets. All three guns of each turret were placed in a single slide and had combined elevation aiming. Thanks to the identical turrets, they proved to be interchangeable. For that reason, the main battery guns of Arizona—which have rested at the bottom of Pearl Harbor since December 7, 1941—managed to rain down fire on the enemy that had destroyed her. Three of the guns, those in the fore turret, can still be found on the destroyed battleship. Another of her six guns, along with the aft turrets, were demounted from Arizona during the war and used to create the coastal battery in Hawaii. Three guns of the second turret, which had been damaged by heat from fire on the ship, were restored. In the autumn of 1944, they were placed in the fore turret of battleship Nevada and used to crush the Japanese fortifications on Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

The transition to 406 mm main guns in the U.S. Navy happened on four Colorado-class battleships that were laid down between 1917 and 1920. Created as a "16-inch version" of the preceding Tennessee-class super-dreadnoughts, these ships only differed by their artillery. The new 406 mm/45 Mark 1 guns were placed in four twin-gun turrets, which were almost identical to the triple turrets with 356 mm guns of their predecessors in terms of their design. The gun elevation angle was 30 degrees, which allowed them to fire a 957 kg shell over distances of up to 31,000 meters. In terms of muzzle energy—a parameter that's relevant to the armor-piercing capabilities of a shell—the new artillery system was twice as powerful as the 305 mm Mark 7 main guns of dreadnoughts Wyoming and Arkansas, which had been commissioned in 1912, and 50% more powerful than the 356 mm Mark 1 guns of the Pennsylvania-class battleships of 1916. However, the Colorado class were the only ships in the U.S. Navy that carried 406 mm Mark 1 guns: the Washington Naval Conference of 1921–1922 ended with the greatest powers declaring a 10-year pause or "holiday" of the construction of capital ships.

The 406 mm/50 Mark 7 guns—the main battery of the Iowa-class battleships, as well as the Montana class which were never built—were probably the best artillery assets ever to be used on capital ships. Their super-heavy 1,225 kg Mark 8 AP shells had an effect comparable with the 460 mm ammunition of battleship Yamato, while being considerably lighter. The matter of choosing the main battery for the fast battleships of the U.S. Navy caused a great many discussions in 1938.

On one hand, the 406 mm/45 Mark 6 guns designed in the mid-1930s for the preceding North Carolina and South Dakota-class battleships were already considered to be the most powerful in the world. Compared with other large-caliber guns, they fired very heavy 1,225 kg shells that had a relatively modest initial velocity of 701 meters per second. The shell trajectory was more of an arcing one, and no armored decks of any existing ships were capable of withstanding these shells when fired from significant ranges. Because of this, there were no specific reasons to replace these guns with something new.

On the other hand, depots in the U.S. stored over one hundred of the 406 mm/50 Mark 2 guns that had been produced throughout 1918–1922 for battleships that went unfinished due to the Washington Treaty on the limitation of naval armament. Owing to a longer barrel length, they possessed very high muzzle energy. This enabled an increase in armor penetration and firing range for the main guns of new ships with small material inputs. Lastly, the Naval Bureau of Ordnance proactively worked on the development of new 406 mm/50 guns that were lighter and more modern. This last factor resolved the issue: according to the estimates, the Mark 2 gun was significantly heavier than the Mark 6 and it required a bigger turret for mounting. This meant an increase in water displacement that would affect the major characteristic of future battleships—their top speed. Having considered all the factors, the General Council of the U.S. Naval Forces decided on the new guns for the main battery.

Reward

Completing this sub-collection provides the following rewards:

| Icon | Name |

|---|---|

|

Stars |

"Always Courageous" Collection - Naval Uniforms from World War II

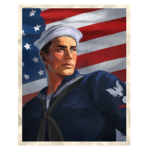

A signalman communicating a message using flag semaphore, wearing probably the most well-known outfit of a U.S. navy sailor or petty officer—the undress service uniform. In summer and in hot climates, the personnel wore a shirt and trousers made of paper-cotton cloth. During other seasons and in colder weather conditions, a shirt and trousers made of blue woolen cloth were used. Interestingly, the well-known bell-bottom style trousers of a blue color had wider pant legs than those of the white color. In fact, this was the only difference between the white and blue undress service uniforms, but traditionally, the former was connected to the image of a sailor from the Pacific Ocean and the latter to one from the Atlantic. As opposed to the dress service uniform, it did not have cuffs with distinctive insignia and stripes and stars on the collar. Surprisingly, a meaningful message was conveyed by wearing a black silk neckerchief. If it was absent, that meant that the sailor was engaged in their standard ship duties; if it was present, it meant that the sailor was in full dress and on official duty—they even could go on shore wearing this outfit. Sailors were quite satisfied with this uniform as it was in line with the more elite atmosphere compared with other U.S. military branches. Indeed, one could hardly confuse a sailor with anybody. The only problem was the insufficient number of pockets on a sailor's duck blouse and trousers.

Signal officers communicating with the help of a searchlight. In accordance with the U.S. Navy Uniform Regulations, when a ship was at anchor, the crew could only appear on the upper deck wearing an undress service uniform. When working in the engine room, gun turrets, and other internal compartments, the personnel had to wear a special uniform—a light-blue paper-cotton shirt and dark-blue canvas trousers. However, from the early days of the war, sailors began to increasingly wear this working uniform as their regular attire onboard while on duty and in combat. This was officially approved by the commanders who were in no way bothered by the absence of any distinctive insignia on the uniforms. Loosely fitting, durable and dirt-resistant cloth, with plenty of pockets and a belt, this uniform was very comfortable for daily routine services. This is how the iconic outfit of a U.S. Navy sailor originated—a worn-out, faded shirt, trousers of different tones of blue, similar to jeans, and rolled up pant legs and sleeves, which was strictly forbidden when wearing the undress service uniform. On top of that, sailors wore a white "dixie cup" cap rakishly tilted over the back of the head, despite the standard requirement to wear it upright.

Petty Officer 3rd class—electrician in a dress service uniform. The uniform shirt with a square turn-down collar and trousers were made from woolen cloth of the so-called navy blue color—very dark, almost black. A black silk neckerchief was a mandatory element of the uniform. This type of uniform, worn by all sailors and petty officers—except the chief petty officer—had three white stripes on the sides of the collar, and a white star on each of its lower corners.

Petty officer distinctive insignia and specialty signs in the form of sleeve chevrons were located on the honorable right sleeve of the uniform used by servicemen who operated on the upper deck—the boatswain's crew, gun fire-control system operators, gunner's mates, signal officers, torpedomen, helmsmen, etc. As opposed to the upper-deck officers, their lower-deck crew mates—electricians, gunners, aviators, machinists, storekeepers, etc.—had their chevrons on the left sleeve. However, in accordance with the U.S. Navy Uniform Regulations of 1941, the eagle's head on the petty officer's sleeve chevron must always face forward. Therefore, when we look at the chevron on the left sleeve, the eagle's face is turned to the left, and when we look at the chevron on the right sleeve, the eagle's face is turned to the right.

The service dress uniform also included a dark-blue sailor cap, but American sailors preferred the much more popular white "dixie cup" caps with an upright brim. The name of this cap refers to the name of a manufacturer of white disposable cups that had a similar shape.

In cold weather, U.S. Navy sailors and petty officers wore a dark-blue woolen double-breasted short coat with 10 large plastic buttons with anchors. A wide turnover collar and high-positioned slash pockets protected those who wore it from wind and cold—the coat was worn both at sea and on land. The stylish design made this coat popular among civilians and it still remains popular today. The short coat was usually worn with the dress service uniform. Sometimes, especially at sea, sailors put on a sweater under the coat to keep warm. In winter, sailors usually wore a dark-blue woolen sailor cap with a ribbon around the cap band, which had the words "U.S. NAVY" printed and shining on its front side in golden letters. It wasn't very popular among sailors who preferred the "dixie cup" cap instead and gave it a disrespectful nickname—"Donald Duck"—for the resemblance to the cap worn by the cartoon character. However, climate played a key role in choosing headgear, and in Great Britain during the World War II era, the image of an American sailor was inseparable from that of Donald Duck. And of course, this image was complemented by a huge canvas bag with personal belongings. No wonder this bag, along with the winter short coat, have been used to create the iconic image of a "lone sailor" embodied in well-known monuments devoted to U.S. Navy sailors.

Reward

Completing this sub-collection provides the following rewards:

| Icon | Name |

|---|---|

|

Stars'n'Stripes |

Overall Reward

Completing the entire collection provides the following reward:

| Icon | Name | Notes |

|---|---|---|

|

Oklahoma | American premium Tier V battleship A Nevada-class battleship belonging to the first series of the U.S. Navy's Standard-type battleships. Oklahoma had "all-or-nothing" armor protection, and her main battery guns were concentrated at her fore and aft ends. |

| Icon | Name |

|---|---|

| |

6-point US Commander |

| Icon | Name |

|---|---|

|

Military - Oklahoma |

Category: